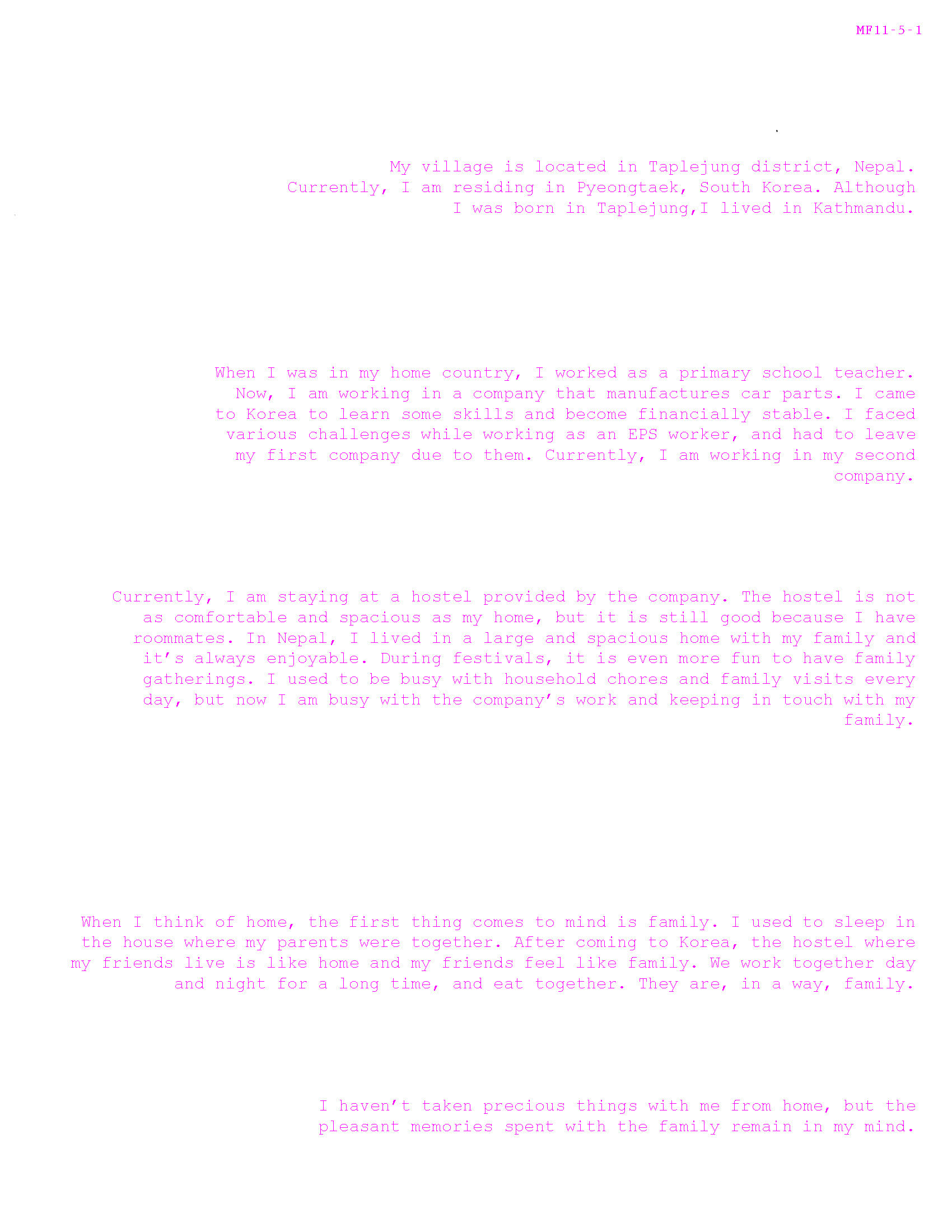

N H D M Architects, A Home is Not a Vinyl House (Domicile #1), 2023, print on paper,

93cm x 62cm.

Migrating Futures

| Commission |

| 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale “The Laboratory of the Future” |

| Type |

| Research, Design, and Exhibition |

| Support |

| Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts |

"Migrating Futures" (이주하는 미래) is an ongoing project by N H D M that investigates the historical and contemporary geographies of diverse diaspora communities and transnational migrant workers within Korea and across Asia. While often subjected to the enduring colonial legacy of subjugated and racialized laboring bodies and their extremely precarious work and living conditions, the ostensibly transient global subjects shape and embody the emergent and hyper-local spatial typologies, new socialities, and potently intersectional cultural and agentive capacities.

Ansan and the network of similar peri-urban and rural migrant enclaves around Seoul, Korea, the focus for the material shared in this exhibit, represent typical yet underrecognized satellites and archipelagos of uncertain temporalities that exist around many of the developed Asian metropolises, where the vulnerable but resilient populations at the hidden margins support the continual growth and reproduction of the center. Presaging the much more itinerant lives of the future that may be precipitated by climate change or other dissolution of environmental and socio-political norms, and provoking the possibilities of trans-cultural and lateral co-existence beyond the existing national and religious borders and geopolitical hegemonies of the global north and the West, the spatiotemporal landscapes of migrants in Korea provide an opportune testing ground to investigate the futurity of migrancy, territorial mobility, and identity.

Engaging the specifics of the migrant and diaspora population and their spaces in Gyeonggi-do, the most populous and still growing region in South Korea surrounding the capital, the work presented in this exhibition aims to provoke the possibilities of future communities shaped by the new frameworks of labor and belonging. Through the collaboration with local immigrants and migrants communities, artists, and labor and human rights activists, the project initiates a dialog that documents the existing conditions of transnational mobility and the global landscapes of capital-driven migrancy, to consider counter futures of migrant subjects that challenge the historic norms of subjection, settlement, and the geopolitical and economic hegemony.

List of Work

Domiciles Drawings

Three composite drawings, A Home is Not a Vinyl House (Domicile #1), World-Goshi-Chon (Domicile #2), and A Machine for Living In (Domicile #3), describe the three most prevalent informal living situations currently experienced by many migrant workers in Korea, respectively describing a modified polyethylene grow tunnel where many rural seasonal agricultural workers are housed, a Goshiwon (rentable study rooms) in an urban setting usually serving as an initial housing solution for the newly arrived, and shipping container dormitories in small manufacturing sites.

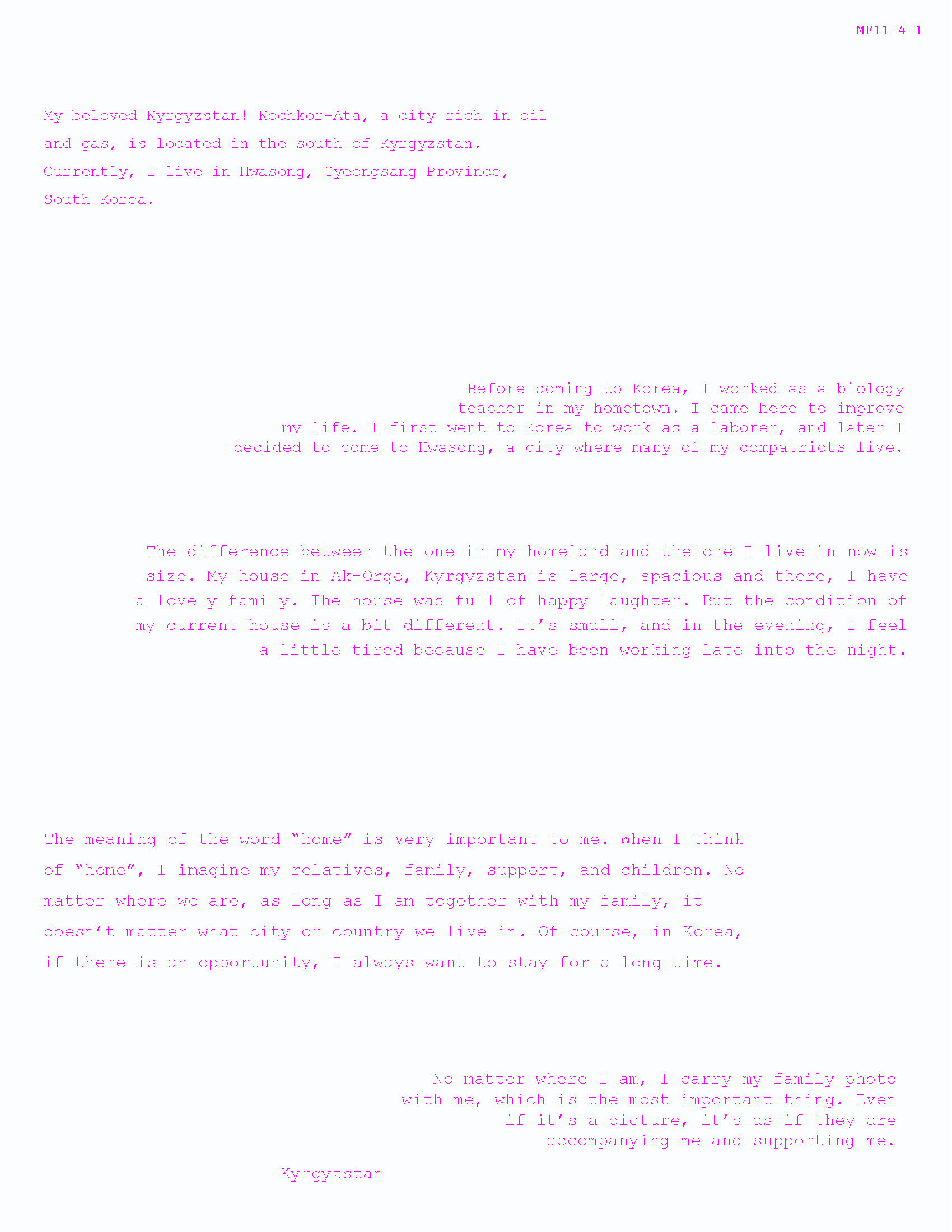

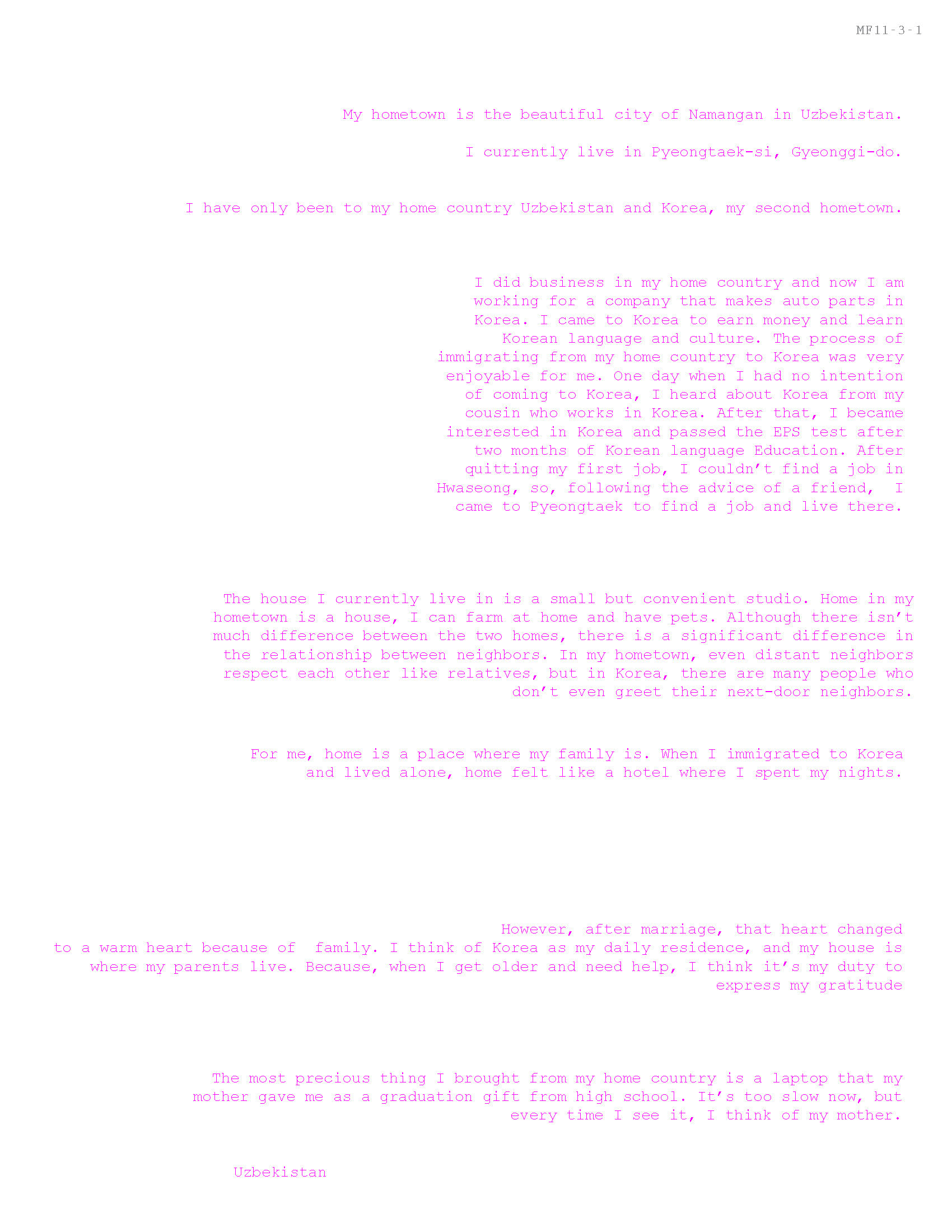

A Home is Not a Vinyl House (Domicile #1) (shown at the top of this page) depicts a typical dwelling situation experienced by many seasonal transnational migrant agricultural workers in rural Korea. Hidden inside the covered-up grow tunnels and camouflaged among crops, the lives inside the "(Vinyl) House," a colloquial term for the plastic greenhouses propagated since the 1960s, is often without basic necessities such as electricity, heating, and water. Frailly layered with what migrant workers call the "sponge house" roughly put together from lightweight foam panels, the low-density polyethylene membranes of Vinyl Houses not only produce the anthropogenic petro-chemical environmental bubbles of constructed atmospheres of controlled climates and pesticidal interiors across much of the available agricultural ground in Korea but complete the plantationocenic enclosures of transplanted labor and their precarious lives. "A Vinyl House is not a Jib" is a common slogan used by migrant rights activists, "Jib" meaning both the physical structure of a house and the lived experience of a home in Korean. The notions of house and home are not separable in the Korean language and culture while "House" as a loanword popularized in the 60s and 70s assumed to imply the enclosed Vinyl House structure among the rural population.

N H D M Architects, World-Goshi-Chon (Domicile #2), 2023, print on paper, 45cm x 62cm.

Based on the actual spaces observed in the "Multi-Cultural Special Zone" of Wondokdong in the city of Ansan, or so-called "Foreigners' City" located on the outskirt of Seoul, World-Goshi-Chon (Domicile #2) describes a typical hybridized medium scale mixed-use building that constitutes many dense migrant enclaves in small peripheral towns. The top floor illustrates the newly-arrived migrants' living in a goshi-won, the ubiquitous pseudo-temporary residential typology originating from rentable study rooms for studying for the bar or other governmental exams. Also known as the goshi-bang ("test-rooms" in Korean), goshi-wons have mutated over the past few decades to informally house some of the most vulnerable populations in Korea including homeless elderly people, youth with no permanent homes, as well as migrants and new immigrants. Amalgamated with these fragile domestic realms are both the spaces of the Im/migration Industrial Complex such as trade training classes for visa changes, job brokers, and remittance vendors, as well as places of diasporic longing and connection to home and one's own culture including spaces of worship, as well as support infrastructures like non-profit organizations. Taking after the urban phenomena of goshi-chon, or so-called "test villages" consisting of restaurants, leisure spaces, and basic amenity businesses, etc. that usually spring up around Goshi-Wons, the migrants' enclaves may be understood as World-Goshi-Chons, the globalized but hyper-local villages of survival and competition as well as of resilience and community.

N H D M Architects, A Machine for Living With/In (Domicile #3), 2023, print on paper, 69cm x 62cm.

A Machine for Living With/In (Domicile #3)portrays a typical small peri-urban manufacturing site, where contract foreign workers are illegally housed in shipping container dormitories. Barely distinguishable from neighboring cargo containers filled with materials and goods, the shipping container dorms and the cheap labor that they afford are hidden but integral parts of the maximized profit machine. The migrant workers live with and in the vibration, noise, heat, and polluted air particles of the unending production, and inhabit the spaces of transnational mobility and the capital and commodities flows as a fully materialized reality.

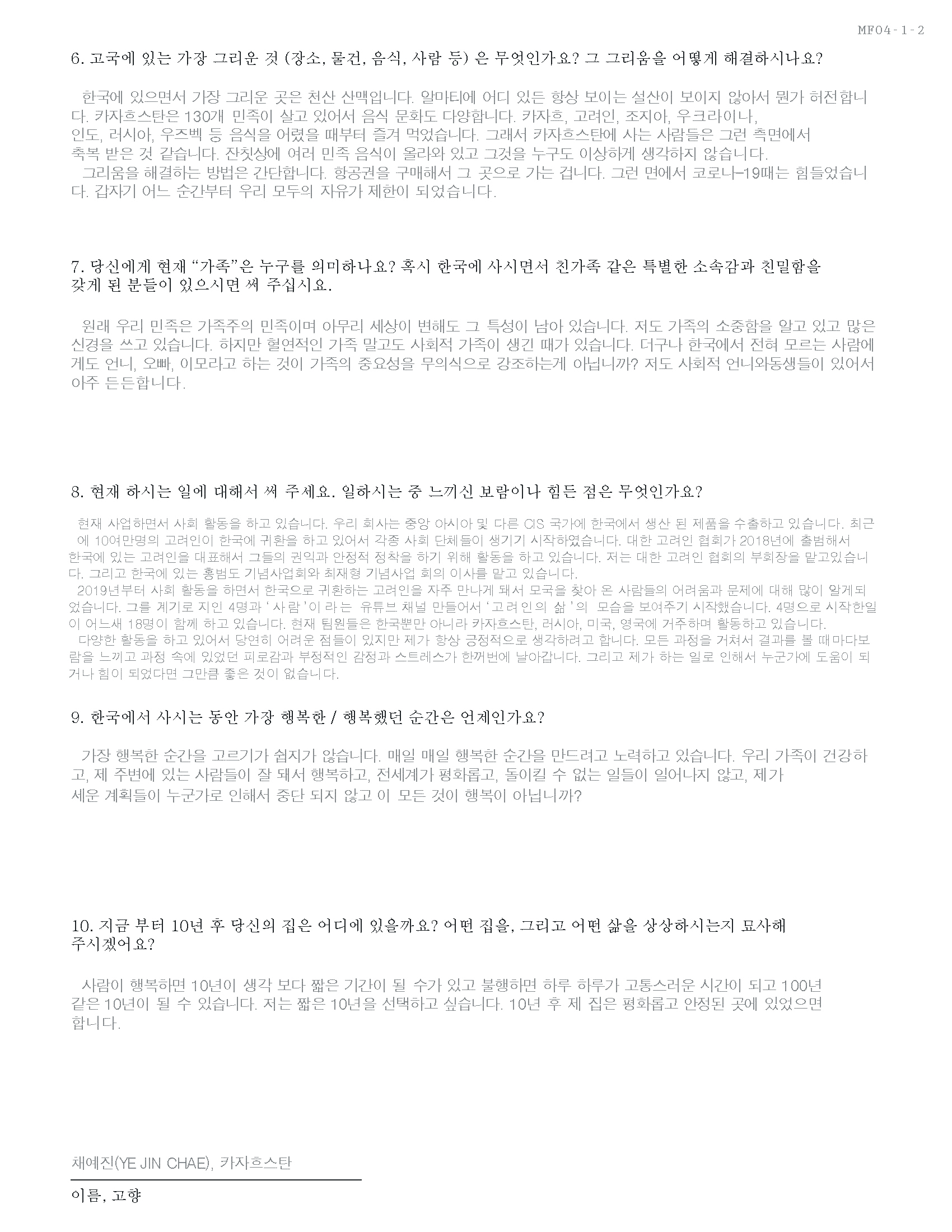

Home is

Excerpts from N H D M Architects with Contributors to the Migrating Futures Survey Project, Home Is, 2023, 86 double-layered 21cm x 29cm transparencies print

The first series of Migrating Futures Survey Project "Home is" engages members of diverse migrant and immigrant communities residing in Gyeonggi Province to document their evolving notions of home as well as the realities of their dwelling. Materials presented at the Biennale are selected from survey answers, interviews, photographs, drawings, poems, letters, and essays, collected from more than twenty-four immigrant and migrant organizations and eighty individuals, responding to prompts to reflect on the meanings of home, belonging, and future.

Collaborators include: People of Earth's Station Ansan (with 박은비), Bucheon Migrant Welfare Center, Asia Media & Culture Factory, International Mongolia School of Korea, Hwaseong Immigrants Community Service Center, Gyeonggi Institute of Research and Policy Development for Migrants' Human Rights, Pocheon Nanum House, Geumcheon Global Migrant Center.

Contributors include: 비스누, Ansan 땟골 임페리아베이커리 사장님, PHAM MINH THƯ, 중국동포(남성분), Ramesh Sayan, Bishnu Wagle, Saroj Sarbahara, Longling, Ansan Shelter-Anonymous worker 1, Tey, Ansan Shelter-Anonymous worker 2, Ansan Shelter-Anonymous worker 3, 따나, Ansan Shelter-Anonymous worker 4, 도스톤, 리자, Adetriana Lolitasari, 채 예브게니야, 슈먼, 아리오나, Canolin, Bikash Shevrma, Ghorshiree Jagdish, Hiraleee, 류홍혜, 부천 Anonymous, 아르민, Dream, Jenny, KIM HAI, Jeon EunJu, Dilip Bantawa, 아마리 미호, 삼토시 아디켄크, Manish, Gyenendva Bafnef, 리즈완, 서자나, 아크말, and Rado.

Six Scenes from Migrating Futures

Inspired by the artistic traditions of various Asian origins where carefully constructed landscape imageries elucidate the critical environment that co-constitutes one's ideological as well as physical journey, and provoked by their layered assemblage that is both the re-presentation of the existing and the framework for alternative-world-making, "Six Scenes from Migrating Futures," the drawings in the hexaptych formation, describe six anthropocenic landscapes of migration of multivalent timelines and identities, seeking the spaces of empathy and the possibilities of new comunality.

Ansan Series—Measure Island (Ansan #1), Take the 4 Train (Ansan #2), Banwol Archipelago (Ansan #3)--- depicts the past, present, and future geographies of migrancy set around the eponymous industrial town, often referred to as "Foreigners' City" or "Migrants' Town" by Korean nationals.

Three additional drawings interwoven with the Ansan scenes—A-Pa-Tu (Keeping House), Head of Two Waters, and Masuk Moru—explore possible futures unfolding at three sites related to three types of transnational migrant work most common in Korea, respectively engaging the space of domestic care, small-scale factory production, and agricultural labor.

Banwol Archipelago (Ansan #3)

Ansan has been a space of coexisting yet divergent utopias, a testing ground for different idealisms. The ambitious terraforming of the Banwol Industrial Complex in 1977 was accompanied by the very first “New Town” in Korea, erected in the familiar blueprints of Howard's Garden City and Wright's Prairie Style homes, to welcome newcomers while displacing the existing population. The same footprints now hold ever-growing apartment towers that promise secure investments and pleasant living for native Koreans, while the factory jobs that Koreans avoid become a tentative basis for the “Korean dream.” In the drawing "Banwol Archipelago," the City of Ansan is partially submerged creating a network of islands at the site of the Banwol Industrial Complex, producing a new aqueous collective ground for human and more than human migrating communities. Each island builds on the existing communal spaces and monuments that predate the factories, while the underwater factories become a refuge for a growing number of flora and fauna and the toxicity of its industrial past becomes a foundation for a new habitat.

Take the 4 Train (Ansan #2)

Prompted by the influx of foreign factory workers in the 90s, Ansan's Wongokdong, or “Wongok Multicultural Special Zone” as the government calls it, grew to be a home away from home for many migrant workers and others in the diaspora. The im/migrant population in Korea has been steadily increasing for the past decades as Korea's Ministry of Employment and Labor systematically recruits low-wage, often ill-treated workers through the "Memorandum of Understanding" co-signed with sixteen developing countries, and increasingly more immigrants and refugees enter the country fleeing economic, political, and climate hardships. The 4 train, connecting Ansan to Seoul, has become a collective route of weekly rituals for these foreigners, allowing them to visit ethnic restaurants and places of worship, and occupy public spaces for cultural expressions and political actions. Inspired by the enclaves of hybrid cultures and places of intersectional care and support spontaneously sprung up along the line, "Take the 4 Train" depicts an imagined future that may grow from such communality, where the train line and its surrounding areas become an unbounded extra territory, where borders are eroded and all cultures are celebrated beyond the constrictions of a "Zone."

Measure Island (Ansan #1)

The small island at the foot of Ansan is called "Measure Island" (형도 or 저울섬), as for many generations locals have been gauging the changes in the ebb and flow of the sea against the island's complete and round shoreline. Starting in the 80s, however, the island's consistent topology started to erode. In 1985, the construction of an immense seawall erected to secure the water supply for Korea's very first national manufacturing zone "Banwol Industrial Complex" mined away the sacred peak of the island as raw material. The persistent "reclamation" of the surrounding land that followed it gradually turned the island into a part of the mainland displacing most of the islanders who lost their long-held ways of life as fishermen. Reflecting on the relationship between manmade shifts of land, water, and people, the drawing conflates the not-so-distant future of the island and the stories from its parallel pasts and presents. Most of the built-up land is underwater due to the rising water level and the Island is surrounded by the sea again. An elderly fisherman from the North, who settled on the island after the war, flees his home once more chasing the disappearing sea. A Korean migrant worker rests after arduous labor to "reclaim" a foreign land in the 1980s Middle East.

A-Pa-Tu (Keeping House)

An ultimate instrument of personal, often inherited, wealth accumulation, and a monument to the sustained corporate growth aided by governmental policies, the overbuilt residential highrises, or “A-PA-Tu” complexes, occupy much of the buildable surface of Korean cities and countryside. Their endless construction and demolition form violently cyclical yet ubiquitous man-made landscapes of what Koreans call "Forests of A-PA-Tu" perpetually growing upwards and materializing the optimized spaces of reproduction for the idealized units of nuclear families. Less visible are the realities of domestic labor and care work performed more and more by foreign women in the global care chain. Occupying the precarious spaces of what some call “an international division of reproductive labor,” the domestic intimate worker's life is much less shaped by intimacy than by the formidable structural forces of patriarchy and racial capitalism. "A-Pa-Tu (Keeping House)" describes the scene of vacant and "unkept" A-Pa-Tu buildings of the near future, most likely from the persistent speculative real estate market compounded by the collapse of the prescribed reproductive sphere, currently presaged by Korea's decreasing birthrate. The empty towers become an opportunity for new inhabitants and new environments, or finally homes for their keepers.

Masuk Moru

Masuk, a renowned furniture factory town in the eastern Gyeonggi province, represents the quintessential rural post-industrial manufacturing town at the periphery of Seoul, where schools close due to the staggering population decline and the plans for large-scale development threaten the fabric of its small-town life. Masuk, however, is also a rare site of intersectional solidarity. The inhabitants and carers of the long-historied Leper colony have been embracing the foreign factory workers as part of their community, offering a sanctuary from labor abuse and other difficulties of migrant life for the past decades. "Masuk Moru" portrays a future scene of one of many currently vacant elementary schools in the area. While providing opportunities for learning, schools have also been places of didactic nationalism throughout Korea's modern history, foregrounding the ideologies of the nation-state in the minds of the next generation. The school is now cared for and inhabited by transnational dwellers, who are able to negotiate new climates with the old environment, nomadism with placeness. Hosting distant geographies and different epistemologies, the bare yet recognizable architecture of the typical Korean classroom frames the exchange and production of new knowledge and a new starting point that is shaped by different notions of belonging and work.

Head of Two Waters

Originally a symbolic yet modest confluence of two rivers—one from North Korea and the other from the South— the water body of Head of Two Waters swelled to today's immense expanse in 1972 when the military government constructed one of the first dams in post-war Korea to secure water, electricity, and flood protection for Seoul, inundating the fragile fluvial landscapes and small farming communities while enabling the fabled "Miracle of Han River" for the capital. Today, the scenic area is a popular site of eco-tourism, while the surrounding greenhouse agricultural industry thrives on a large, often exploited, migrant labor population. Head of Two Waters conflates these hidden stories of water, land, and labor with the parallel stories of the Tonlé Sap ("Fresh River") region in Cambodia that holds a seasonal labor supply contract with Head of Two Waters' government and is home to many agricultural workers like Sokhang, a young laborer who perished tragically in a "vinyl house" dorm. The dramatic reduction of precipitation due to climate change and deforestation threatens the Mekong River region known for its annual inundation that used to replenish its farming ground, forcing its people to cultivate unfamiliar land abroad for remittance. Presaging the fluctuating water levels and climates along the Han River in coming decades, Head of Two Waters imagines a future, when the destabilized geographies produce a new common territory and different land tenure beyond the property and identities, where new relationships between the land and among the people who cultivate it may form.

Project Team: Nahyun Hwang, David Eugin Moon, Chaewon Kim, Myungju Ko, Kevin Hai Pham, Farah Alkhoury, Yoonmin Jo, Hyejin Choe, Aiden Ko, Helen Winter.